I feel a bit ashamed to admit this, but I had never fully watched Akira all the way through until recently.

My ADHD-rattled brain just couldn’t stay focused during the slower scenes. But the other day, I sat down to watch it with a friend who hadn’t seen it before — and for the first time, I found myself fully engaged. I think it was because I was trying to get him to pay attention, but ironically, he ended up doing exactly what I used to do: drift off.

He recognised that it was a great story and that the art was fantastic, but our millennial brains just aren’t used to the slower pacing of an ’80s movie. Still, after a few attempts over the years, I can finally agree with everyone else — this is a fantastic anime film that truly stands apart from the manga.

I’ll be honest: I’m a manga-first kind of person, and I’ve read the first half of Akira. You know the ones — those big, iconic volumes with the two-tone colour schemes, white and red or white and green. Anyone who’s stepped into an anime shop has probably seen them. They’re practically a rite of passage.

Akira Movie Facts And FAQ Audio Blog

For the visually impaired and the too lazy to read without pictures crowd.

Plot of Akira, Simplified

Skip this part if you haven’t seen the film or read the manga.

Spoilers ahead.

In the year 2019, Neo-Tokyo is a chaotic metropolis built on the ruins of Tokyo, destroyed by a mysterious explosion 31 years earlier. The city is overwhelmed by political corruption, anti-government protests, and gang violence.

Amid the unrest, a teenage biker gang led by Shotaro Kaneda tears through the streets. During a clash with a rival gang, Kaneda’s childhood friend, Tetsuo Shima, crashes into a strange, childlike figure with an aged face an escaped government test subject with powerful psychic abilities. Moments later, the military seizes Tetsuo and takes him to a secret government facility.

Inside the lab, Tetsuo is subjected to experiments that awaken immense psychic powers within him. As his abilities grow, so do his feelings of inferiority and resentment especially toward Kaneda, who has always treated him like someone who needed protecting. Tetsuo becomes increasingly unstable, plagued by hallucinations, violent outbursts, and a desperate need to learn the truth about Akira—the mysterious figure linked to Tokyo’s destruction decades earlier.

At the same time, Kaneda teams up with Kei, a member of an underground resistance group, to track down Tetsuo and expose the government’s secret program involving psychic children. But the resistance is fractured and ineffective, and it soon becomes clear that Tetsuo himself is the real threat.

Driven by obsession, Tetsuo breaks free in search of Akira’s remains, which are sealed in a cryogenic chamber beneath the newly constructed Olympic Stadium. As his powers spiral out of control and his body mutates grotesquely, the military makes a final attempt to stop him relying on the Colonel and a powerful orbital weapon as their last line of defence.

In a climactic showdown amid the ruins of the stadium, Kaneda confronts Tetsuo as his powers spiral completely out of control. Just as destruction seems inevitable, the surviving psychic children from the Akira project summon the essence of Akira himself. In a blinding flash of light, Akira returns and pulls Tetsuo into another plane of existence an act that may be mercy, rebirth, or something beyond human understanding.

The film ends with Neo-Tokyo once again in ruins, but this time with a faint glimmer of hope. Kaneda survives, and Kei suggests the possibility of a new beginning. In the final moment, a voice, Tetsuo’s, quietly declares, “I am Tetsuo,” hinting that he has transcended into a new form of existence.

The Visuals of Akira

Akira is 90s anime at its peak, undoubtedly inspiring millions in the West to dive into the world of anime and even pursue art themselves. It helped shift the perception of animation: no longer just for children, but a serious art form worthy of respect.

The film’s art direction (led by Katsuhiro Otomo and his team) and its cyberpunk themes have left a lasting impact. You can see its influence in other iconic works like Ghost in the Shell, which borrows heavily from Akira’s moody tones and visual language.

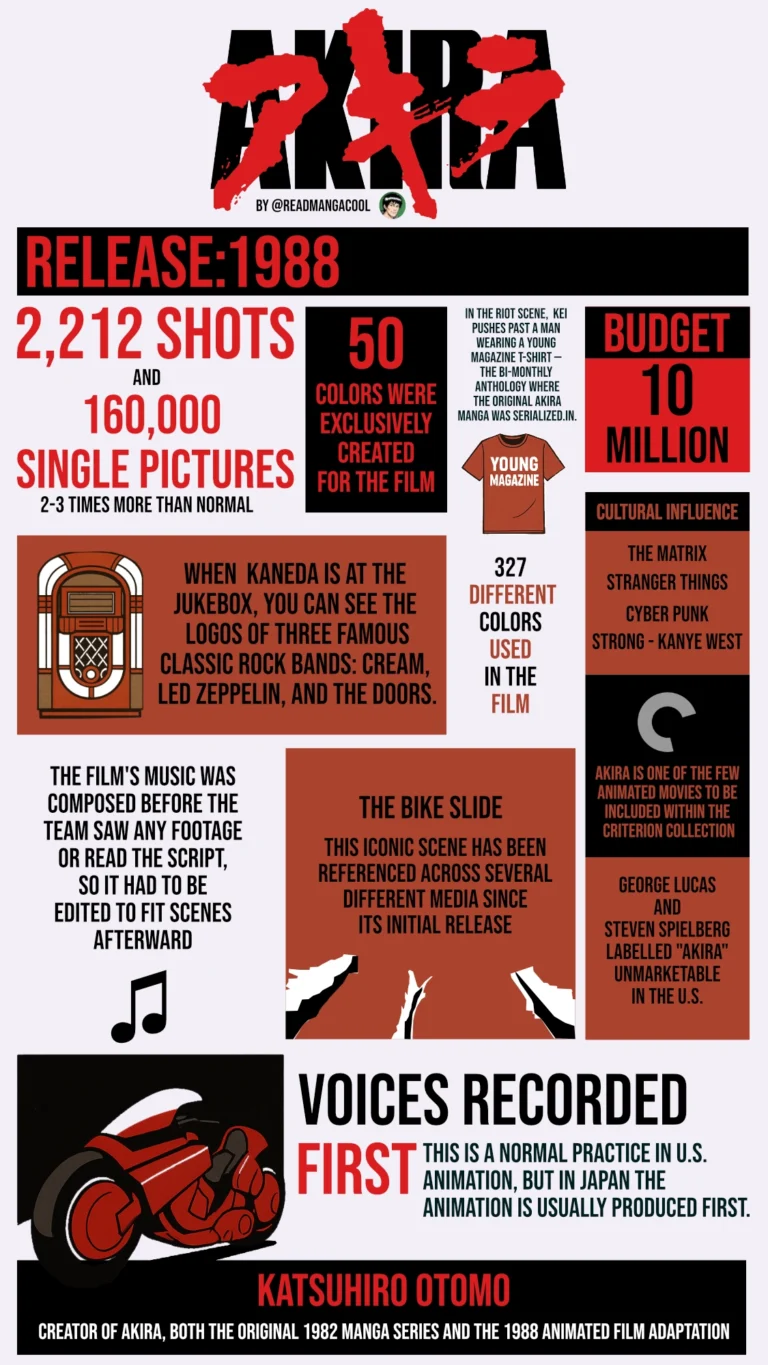

Even modern anime, like Cyberpunk: Edge runners, echo its style mixing the pastel shades of a crumbling inner city with the saturated glow of neon lights, all wrapped in darkness. The animators behind Akira even created 50 brand-new colours just for the film, pushing visual storytelling to new heights.

The hyper-detailed drawings in Akira make everything feel more real. The environments are unique and richly textured, far beyond what you see in most anime. The highly detailed backgrounds make the world feel tangible, with shadows and lighting that behave just like they would in real life. Even today, scenes like the famous night time sequences still look incredible.

It’s amazing to think that artists spent countless hours creating all of this by hand, frame by frame.

If you want to learn more about how Akira changed the game in animation, check out the Corridor Crew video that breaks it all down.

Akira’s Story: A Slow Burn with Impact

Having read part of the manga (the library I used to go to only had the first five of those huge volumes), I can say the anime stays pretty true to the original story. I’m a manga-first, anime-second kind of guy, and while some scenes were cut, they don’t really affect the flow or feel of the story. That said, you always lose a little something when you move away from the source material.

As I mentioned above, the average millennial might find it hard to stay focused, as the story shifts between quiet, slow-moving scenes and bursts of hyper-violent action. Some of the slower parts might drag a bit too much, but that’s where the art really shines, and the payoff at the end helps bring it all together, even if the ending is a little ambiguous.

The Weight of Akira

Watching Akira is the kind of experience that can make you fall in love with animation and the possibilities of true storytelling. It shows how animation can be real art. I was amazed by the quality of the drawing and animation, every frame feels hand-crafted and alive.

The movie has a vibe similar to Blade Runner, a great introduction for anyone discovering serious anime for the first time. It helps break the idea that animation is “just for kids.” That futuristic, apocalyptic atmosphere, with dark shadowy scenes lit by bright neon colours, really hits. It makes me believe in a bleak future, especially when you look at how little the world changes and how mankind’s obsession with science often leads to destruction.

The small, dark, enclosed scenes give off a strong sense of claustrophobia, especially when contrasted with the big, sweeping set pieces that make you feel like something much larger is at stake, not just a small, contained story.

That said, the pacing is slow. It builds gradually, with moments of intensity and long pauses in between. For my millennial-turned-ADHD brain more in line with Gen Z attention spans, I’ll admit it was still tough to focus at times. I got bored during the slower moments, but I don’t blame the film. That part’s on me.

Meet the Akira Creator: Katsuhiro Otomo

The artist, author, and director behind Akira are all one and the same: Katsuhiro Otomo, the first ever manga artist to be inducted into the American Eisner Award Hall of Fame. He’s also received the Purple Medal of Honor from the Japanese government and was named a Chevalier of the French Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.

In addition, Otomo received the Winsor McCay Award at the 41st Annie Awards in 2014, and the Grand Prix de la ville d’Angoulême in 2015, the first manga artist to ever receive that honour. That’s a long list of awards, but well deserved for someone so influential in manga, animation, and pop culture worldwide.

He first published the Akira manga in 1982, and just six years later, he was directing the film adaptation of his own work. But how did he get there?

At age 25, Otomo spent the equivalent of £25,220 (or $34,338.89 in 2025) to produce a one-hour live-action film. The project, though private and not publicly available, taught him how to create and direct films — an experience that would shape his career.

His anime debut came as a character designer for the animated film Harmagedon: Genma Wars. It was during that project that Otomo began to believe he could direct a film himself.

In 1987, he directed animation for the first time: a segment he also wrote and animated for the anthology film Neo Tokyo. Then in 1988, he directed Akira — condensing the plot of the manga but keeping many key characters, story elements, and themes, while adding new scenes and settings unique to the film.

Akira was released on July 16, 1988. It became the sixth highest-grossing Japanese film of the year, It topped the box office upon release and was a clear success in the domestic market. By 2000, it had earned ¥800 million in distribution income.

Akira – A Landmark

Akira isn’t just an anime film — it’s a landmark in animation history that redefined what the medium could be. While its pacing might feel slow to modern audiences, the emotional depth, explosive moments, and intricate world-building create an experience that lingers long after the credits roll. The animation remains breathtaking even by today’s standards, and its themes — from political unrest to the dangers of unchecked power — feel just as relevant now as they did in the late ’80s.

For anyone interested in anime, especially the classics that shaped the genre, Akira is essential viewing. It’s more than just a cult hit — it’s a work of art that paved the way for everything that came after. Whether you’re revisiting it or watching for the first time, Akira is a film that demands your attention. Put it on your list — and let it take you somewhere unforgettable.

Check out this review of Neo Tokyo another anime Katsuhiro Otomo worked on.

Leave a Comment